Amiga's Dark Secret

by Bernard Anderson and Chris Collins

FOREWORD

Whereas Jay Miner is the father of the Amiga, Dave Needle is the father of the A1000. He worked on several of the motherboard revisions from prototype to production. He was also there when serial number 1 of the A1000 rolled off the assembly line at the Sanyo factory in Japan.

Dave began working at Amiga Corp. as a janitor but his coworkers soon discovered his technical skills, namely Glenn Keller. His first assignment was converting Glenn’s silicon to wire wrap. Soon he was working on finishing the Agnus chip, taking over for Joe Decuir in late 1983. Although Dave was new to chip design, Jay Miner trained him on the spot.

He claimed he was a Jovian from Jupiter. In addition he created his own language and customs. One example is a concept called a snaught pit, where he would take close friends out to lunch and pay for the meal out of generosity.

Dave returned to his home planet on February 20, 2016. We would like to dedicate this article in his memory.

Amiga Corporation was initially known as a manufacturer of video game controllers, namely the Power Stick and Joyboard. In 1983 they announced a cassette based add-on for the Atari VCS called The Power System. These products were made to increase sales by tapping into an existing consumer base and making contacts in the game industry. As it so happens, there was another system in the works which they had been designing since the company’s inception a year earlier.

In early 1984, word of a new computer began circulating in the press. What was initially conceived as a game console was by this point being reconfigured as a state of the art desktop PC called Lorraine. Amiga were looking to compete with IBM and Apple.

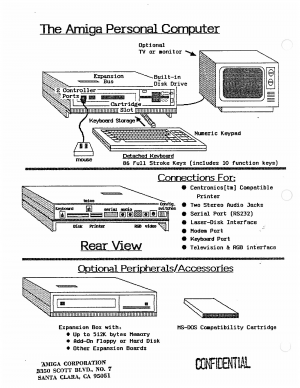

The computer would be a micro with a 320K IBM disk drive, 300-baud modem, four-voice stereo sound with the ability to speak in a male or female voice, and a graphics palette of 4,096 colors. 80 column text could also be displayed on a television set and was reportedly so sharp, it could be read from across the room.

The computer would be bundled with a mouse, however the hardware supported a variety of controllers available to the user: a standard Atari joystick, proportional controller, trackball or light pen. And in addition to its own operating system, Lorraine could run CP/M 68K or the UCSD p-System. An 8088 coprocessor cartridge for running PC-DOS was also announced.

A top port dubbed the chimney allowed an expansion box to be connected. The box would expand the memory to 512K, have slots for expansion boards and a bay for either a second floppy drive or hard disk.

The expansion chimney is similar to that of another desktop computer being sold at the time, the Mindset. Another similarity is the support for a genlock, a device which allows an external video signal to be synchronized with the computer’s display.

The projected retail price for the Amiga Lorraine computer was initially around $1,000 USD. David Morse, president of Amiga, assured the press and potential investors that this was a real product and provided the early specifications. Morse, due to fears from competitors, was careful to control how much information would be shared at the time. Technical documents related to the computer remained confidential, including the memory map.

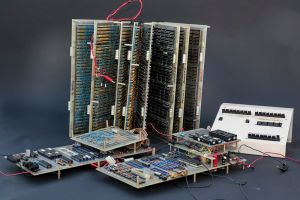

By the time of the ‘84 Summer CES, the three custom chips: Agnus, Daphne and Portia had been made into silicon. Further testing was underway. A new motherboard was also being designed and the wire wrap boards that initially comprised Lorraine would soon be retired.

The first batch of silicon had a chip with a faulty trace. As it had cost a considerable amount of money for the fabrication and time was tight, they couldn’t afford to scrap them.

Dave Needle and Stan Shepard agreed to have the $15,000 they were owed in back pay go toward the chips. So the hardware group fixed the faulty chip using a high powered microscope and cut through it with an X-Acto knife.

Atari, still owned by Warner Communications, were interested in using the chipset, initially in their coin-op division, then in a game console/stealth computer system codenamed Mickey. This project was canceled after Jack Tramiel bought Atari’s consumer division the week of July 1st. It was decided that they didn’t need another 68000 based machine. After all, they had been developing their own, the 520ST.

On August 15th, it was announced that Commodore had purchased the financially ailing Amiga. Rick Geiger replaced David Morse as president. Amiga relocated from Santa Clara to a new building in Los Gatos and were provided with Sun 2 workstations for development.

The Commodore purchase sparked a lawsuit from Atari Corp. This was a countersuit against Commodore, claiming their former employees at the new Atari stole trade secrets when they left. It was around this time that Leonard Tramiel discovered the $500,000 check Atari Inc. had given Amiga and David Morse returned prior to July 1st.

Sometime after Commodore acquired the company, software developers were given preliminary versions of the new computer. Around 100 “black box” development systems were handmade by Amiga in Los Gatos. They were housed in a black metal case and came with a black wooden keyboard.

Early software developers for the Amiga included Electronic Arts, Synapse and Don’t Ask Software, who had developed the S.A.M. speech synthesizer for the Atari 800, Apple II and Commodore 64 computers.

Don’t Ask Software received one of the first units ever made: a grey box, serial number D-002 which featured a reset switch and a different motherboard. DAS and Sam Dicker used it for cross compiling the text to speech interface, which formed the basis for the Say command. Only 3 grey boxes were ever produced. Don’t Ask Software would later change their name to SoftVoice, Inc.

Motherboard designs and FCC testing for the early development systems were done by Dave Needle. Dave, Stan Shepard and Robert Ewell were at the time working as contractors at Amiga. Their company was Software & Hardware Innovative Technologies and the logo was fittingly, a toilet paper roll. Dave had his hands full with PCB layout and mechanical design so he hired Joe Fernandez, a veteran in FCC compliance.

Commodore had developers purchase the development systems. However, they weren’t all being delivered. Frustrated with how this rollout was managed, Dave Needle personally took four of them from the lab and gave them to EA.

Development systems contained preliminary silicon with notes scrawled on them, towers with sockets and various kludges. The chipset still had bugs and there were certain features planned but not yet implemented. Daphne and Portia underwent the most changes during the time the systems were produced.

Software

Software developer Michael Sinz recalls using the black box, “You needed a Sun 2 workstation - it required the chimney hardware, as the only way to get code into the Amiga was by dumping it into the RAM of the Amiga via the Sun.” “The chimney was a really big 68000 bus extender to the Sun - and did “DMA” to the Amiga by grabbing the bus select and holding the 68000 in wait state while the Sun wrote to memory.” A special RAM board with a write protect switch was used in conjunction with the chimney and plugged in the cartridge slot.

Debugging was done through the serial port using Wack, written by Carl Sassenrath. One of its features was bus monitoring: “Wack could do some of that but it was limited by the speed of the Sun 2 hardware in how much analysis it could do of the bus while it was running.” Wack would later be known as ROM-Wack, the resident debugger included with Amiga computers up until OS version 3.0.

Conclusion

After the launch of the Amiga 1000 on July 23, 1985, the development systems were rendered obsolete and decommissioned.